Japanese Animation and New Media

Lecture Two: Chapter Two: Animation Stand

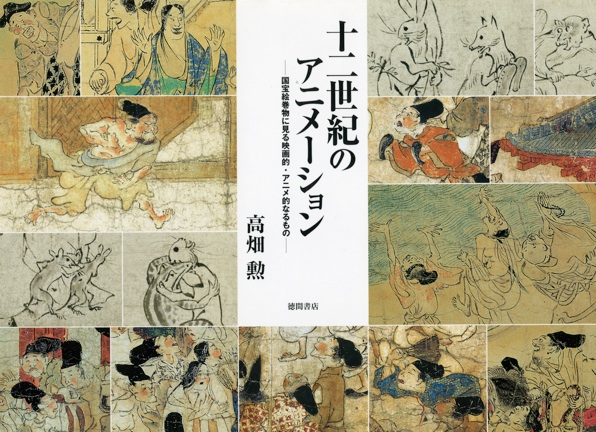

Studies of animation often focus their attention on how the images are drawn. In the context of animation, there is then a tendency to trace a direct line of descent from medieval picture scrolls (emaki) or Edo wood-block prints (ukiyo-e) to contemporary anime. A prime instance is Takahata Isao’s book on Japanese animation called Jūni seiki no animeeshon: kokuhō emakimono ni miru eigateki—animeteki naru mono or “Twelfth-century animation: cinematic and animetic effects seen in our national treasure picture scrolls” (Tokyo: Tokuma shoten, 1999).

As you can see from the book cover, Takahata finds the origins of Japanese animation in medieval picture scrolls that use lively brushwork to convey motion and emotion of figures. Indeed, there is something ‘comic’ and even ‘cartoonish’ about these figures drawn with simple yet lively lines. They wouldn’t necessarily look out of place in Japanese animation or manga (Japanese comics).

Chôjû jinbutsu giga emaki

Moreover, reading picture scrolls does entail a kind of movement from image to image. But for me the picture scroll isn’t animation, or even a precursor of animation. Emaki, ukiyo-e, and other arts can serve as sources or inspiration for animation. Animation can use drawing styles from these arts or any of a number of other arts. It can even mimic the movement of reading picture scrolls. But technologies of the moving image introduce a relation between image and movement that is very different from that found in picture scrolls and other traditional arts. In other words, picture scrolls can be a source for animation but they are not the source of animation.

This is why, even though I began with questions about how images are drawn or composed in one-point perspective, I did so in order to ask, ‘What happens to one-point perspective under conditions of movement?’ For me, animation is above all an art of movement.

At the same time, I am insisting that movement in animation is different from that in, say, picture scrolls. In other words, I am also insisting that animation is a modern art of movement. It is an art of the moving image.

Generally, when people insist on the modernity of cinema or animation, they talk about the impact of the movie camera and movie projector, calling attention to two things.

On the one hand, they show how modern technologies associated with the moving image introduce evenly spaced intervals between images. Moving images are photographed in order to project them a specific speed with the images appearing sequentially at a fixed rate. In contrast, emaki (picture scrolls) set up certain directions and guides for the movement of reading but don’t rely on even intervals and fixed speeds.

On the other hand, as we have seen, discussions of cinema have frequently dwelled on how the monocular lens of the camera tends to produce images in conformity with the conventions of one-point perspective and even Cartesianism. This is where ‘apparatus theory’ begins, and questions about the specificity of cinema arise (the specificity thesis). Of course, even though the movie camera has a monocular lens, and even if such a lens may imply certain orientations toward the world, you can do anything you want with a camera. You don’t have to produce images with a sense of depth in accordance with one-point perspective. There are lots of ways of creating other effects with cameras. The point of apparatus theory is not to say that the movie camera always inevitably produces one-point perspective or Cartesianism. Rather apparatus theory asked why it is that cinema tended historically toward a kind of Cartesianism, rather than pursuing a range of other possibilities.

Nonetheless, if the apparatus theory of cinema is usually rejected today, it is because it is read as a form of technological determinism. That is, the technology itself held responsible for the directions taken by cinema. It is this kind of apparatus theory that I wish to avoid. Yet I agree with apparatus theory that there are material tendencies built into technologies, or rather, technical objects and technical ensembles. This is what I call technical determination, which is not the same as technological determinism. Technical determination sets up material tendencies and orientations, but it is possible to override them with other orientations. For a technical determination or a set of material orientations to persist, it must be prolonged, reinforced, supported, and extended.